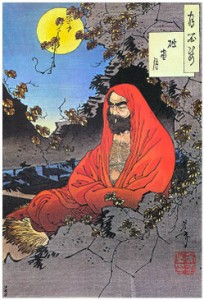

Bodhidarma also known as the Tripitaka Dharma Master, was a semi-legendary Buddhist monk. Bodhidharma is traditionally held in Shaolin mythology to be the founder of the Chan school of Buddhism (known in Japan and the West as Zen), and the Shaolin school of Chinese martial arts.

The major sources about Bodhidharma’s life conflict with regard to his origins, the chronology of his journey to China, his death, and other details. One proposed set of birth and death dates is c. 440 to528 CE; another is c. 470 to543 CE.

Dharma Desi (the “Second Buddha,” Bodhidharma in Sanskrit, Daruma Daishi in Japanese, Hindu Duty in English, and Tamo in Chinese) was an Enlightened Hindu prince from India who engaged in the re-teaching, reaffirmation, and revival of Ancient Hindu philosophy in China, which was originally spread to China by another Indian Hindu Spiritual Leader, Siddhartha Gautama, or Gautama Siddhartha, otherwise known as the “First Buddha” who is recorded as living from 553 B.C. – 483 B.C., and who, like Bodhidharma, began his life as a prince in ancient India.

The First Buddha’s teachings had an enormous effect on the Second Buddha. Those teachings included the Way, which is a method to end suffering through the Four Noble Truths.

The Four Noble Truths are:

- Life is full of pain and suffering;

- Suffering is caused by greed;

- Suffering can be ended if greed is ended; and

- To end greed, people must follow eight basic principles, called the Eightfold Path.

The Eightfold Path is a set of instructions on the proper way to live. Suffering would cease entirely if all people:

- Try to know truth;

- Resist evil;

- Refrain from hurting others;

- Respect life, property, and morality;

- Work without hurting others;

- Free the mind from evil thoughts;

- Stay in control of one’s feelings and thoughts; and

- Focus and sharpen the mind through meditation, i.e., practicing appropriate forms of concentration.

It was this last instruction that Bodhidharma, the Second Buddha, discovered that people had the most difficulty with.

The “First Buddha,” Siddhartha, spread spiritual and meditative Buddhism from India to China to form the first Shaolin Temples.

The “Second Buddha,” Bodhidharma, also known as “Prince Sardilli,” “Dharma Desi” in Sanskrit, or “Daruma Daishi” in Japanese, reaffirmed the First Buddha’s teachings, but who also reinforced those teachings with Martial Arts and regimented physical conditioning to strengthen the mental stamina required for spiritual release, from the earthly and material world.

The Second Buddha, Bodhidharma, began his life in Southern India in the Sardilli royal family in 482 A.D., almost 1,000 years after the First Buddha. In the midst of his education and training to continue in his father’s footsteps as King, Bodhidharma encountered the Buddha’s original teachings. He immediately saw the truth in Lord Buddha’s words and decided to give up his esteemed position as a prince and inheritance to study with the famous Hindu teacher Prajnatara. Young Prince Sardilli rapidly progressed in his Hindu studies, and in time, Prajnatara sent him to China, in order to better teach the inhabitants of China the lessons and rigorous discipline required for a perfect meditative state leading to spiritual release from the earthly and materialistic world.

Upon arrival in a different part of China, the Emperor Wu Ti, a devout Buddhist himself, requested an audience with Bodhidharma. During their initial meeting, Wu Ti asked Bodhidharma what merit he had achieved for all of his good deeds. Bodhidharma was unable to convince Wu Ti of the value of the teachings he had brought from India. Bodhidharma then set out for Luoyang, crossed the Tse River, and climbed Bear’s Ear Mountain in the Sung Mountain range wherein another Shaolin Temple, originally founded by the First Buddha, was located. He meditated there in a small cave for nine years.

Bodhidharma, in true Maha or “great” spirit, was moved to pity when he saw the terrible physical condition of the monks of the Shaolin Temple. It seemed to him that they were unable to fully grasp the enormous mental and abstract discipline necessary to achieve Nirvana, or the ultimate release destination derived from meditation. The monks had practiced long-term meditation retreats, which made them spiritually stronger, but physically weak and unable to finish their meditative journeys. He also noted that this meditation method caused sleepiness among the monks. Therefore Dharma informed the monks that he would teach their bodies and subsequently their minds the Buddha’s dharma, or “duty” through a two-part program of meditation accompanied by excruciatingly difficult physical training. Hence, his appellation of “Bodhidharma”.

Unfortunately, the Chinese Buddhists could not maintain the abstract discipline that this difficult meditation required, and so Prince Sardilli taught them incredibly rigorous physical training, in order to teach them the necessary discipline required for the true Hindu meditative journey leading to “Moksha,” or release from earthly bondage, otherwise known as “Nirvana.” It was Bodhidharma’s theory that, after the physical body was pushed beyond its limits, the mind would begin to take over, and help the body carry through with the physical exertions required for the training. Bodhidharma further postulated that, once this level of mental strength was achieved, the mind would forever be altered, and its capacity for focus and concentration would be fortified. He was correct in his theory, and the Shaolin monks became incredibly strong mentally, and their focus in meditation became unparalleled.

Their minds became harder and more disciplined after these regimented actions. Bodhidharma had arrived in China after a brutal trek over Tibet’s Himalayan Mountains, surviving both extreme elements and treacherous bandits, and he believed that his tutelage was being rewarded with results.

There are statues of the Guardians at the Shaolin Monastery who were trained by Bodhidharma to deflect the negative advances by bandits and hostile Chinese warlords, who sought to disrupt the monks achievement of Moksha, or Release.

Bodhidharma created an exercise program for the monks which involved physical techniques that were efficient, strengthened the body, and eventually, could be used practically in self-defense. When Bodhidharma instituted these practices, his primary concern was to make the monks physically strong enough to withstand both their isolated lifestyle and the demanding training that meditation required. It turned out that the techniques served a dual purpose as a very efficient fighting system, which evolved into a martial arts style given the Chinese name, “Kung Fu.” Martial arts training helped the monks defend themselves against invading warlords and bandits. Bodhidharma taught that martial arts should be used for self-defense, and never to hurt or injure needlessly. In fact, it is one of the oldest Bodhidharma axioms that “one who engages in combat has already lost the battle.”

Thereafter, Bodhidharma, who was himself a member of the Indian Kshatriya warrior class and a master of staff fighting, developed a system of 18 dynamic tension exercises. These movements found their way into print in 550 A.D. as the Yi Gin Ching, or Changing Muscle/Tendon Classic. We know this system today as the Lohan (Priest-Scholar) 18 Hand Movements, the basis of Chinese Temple Boxing and the Shaolin Arts.

Ancient Sanskrit text located in India and China record that Bodhidharma settled in the Shaolin Temple of Songshan in Hunan Province in 526 A.D. The first Shaolin Temple of Songshan was built in 377 A.D. for Pan Jaco, “The First Buddha”, almost 1,000 years after the First Buddha’s death, by the order of Emperor Wei on the Shao Shik Peak of Sonn Mountain in Teng Fon Hsien, Hunan Province. The Temple was for religious training and meditation only. Martial arts training did not begin until the arrival of Bodhidharma in 526 A.D. Sadly, Bodhidharma, died in 539 A.D. at the Shaolin Temple at age 57.

Bodhidharma was an extraordinary spiritual being who remains an example and an inspiration to meditative and martial arts practitioners today. He is the source of many miraculous stories of ferocity and dedication to the Way. One such legend states that Bodhidharma became frustrated once while meditating because he had fallen asleep. He was so upset that he cut off his eyelids to prevent this interruption in meditation from ever happening again. This is a reminder of the true dedication and devotion necessary in meditation practice. Today, the “Bodhidharma doll” is used as a symbol of this type of dedication in Japan and other parts of the world. When someone has a task they wish to complete, they purchase a red Bodhidharma doll that comes without pupils painted on the eyes. At the outset of the task one pupil is colored in, and upon completion, the other pupil is painted. The dolls and the evolution of martial arts and meditation, are a continuous reminder of Bodhidharma’s impact on Buddhism and subsequent regimentation of the martial arts.

Spiritual Approach

Tradition holds that Bodhidharma’s chosen sutra was the Lankavatara Sutra, a development of the Yogacara or “Mind-only” school of Buddhism established by the Gandharan half-brothers Asanga and Vasubandhu. He is described as a “master of the Lankavatara Sutra”, and an early history of Zen in China is titled “Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Lankavatara Sutra” (Chin. Leng-ch’ieh shih-tzu chi). It is also sometimes said that Bodhidharma himself was the one who brought the Lankavatara to Chinese Buddhism.

Bodhidharma’s approach tended to reject devotional rituals, doctrinal debates and verbal formalizations, in favour of an intuitive grasp of the “Buddha mind” within everyone, through meditation. In contrast with other Buddhist schools such as Pure Land, Bodhidarma emphasized personal enlightenment, rather than the promise of heaven.

Bodhidharma also considered spiritual, intellectual and physical excellence as an indivisible whole necessary for enlightenment. Bodhidharma’s mind-and-body approach to enlightenment ultimately proved highly attractive to the Samurai class in Japan, who made Zen their way of life, following their encounter with the martial-arts-oriented Zen Rinzai School introduced to Japan by Eisai in the 12th century.

According to legend, he developed two exercise regimens for the monks of the Shaolin Monastery the “Yi Jin Jing” (Muscle Change Classic) and the “Xi Sui Jingâ” (Marrow Washing Classic) which supposedly became the basis of the Shaolin style of Kung Fu and subsequently an important influence on the martial arts of East Asia in general. However, it is difficult to determine the veracity of the Shaolin legend. The Extensive Records of the Taiping Era record that, prior to Bodhidharma’s arrival in China, monks practiced wrestling for recreation. Shaolin monastery records state that two of its very first monks, Hui Guang and Seng Chou, were expert in the martial arts years before the arrival of Bodhidharma. The exercises attributed to Bodhidharma are consistent with Chinese qigong exercises and look little like Indian forms of bodywork like yoga. Scholarship by Chinese martial arts historians has demonstrated that the Yijin jing and Xisuijing are most likely Ming dynasty (1368-1644) texts due to the presence of technical terminology from the Daoist “inner alchemy” (neidan) tradition which reached its maturity in the Song. This argument is summarized by modern historian Lin Boyuan in his Zhongguo wushu shi.

As for the “Yi Jin Jing” (Muscle Change Classic), a spurious text attributed to Bodhidharma and included in the legend of his transmitting martial arts at the temple, it was writtin in the Ming dynasty, in 1624 CE, by the Daoist priest Zining of Mt. Tiantai, and falsely attributed to Bodhidharma. Forged prefaces, attributed to the Tang general Li Jing and the Southern Song general Niu Hao were written. They say that, after Bodhidharma faced the wall for nine years at Shaolin temple, he left behind an iron chest; when the monks opened this chest they found the two books “Xi Sui Jing” (Marrow Washing Classic) and “Yi Jin Jing” within. The first book was taken by his disciple Huike, and disappeared; as for the second, the monks selfishly coveted it, practicing the skills therein, falling into heterodox ways, and losing the correct purpose of cultivating the Real. The Shaolin monks have made some fame for themselves through their fighting skill; this is all due to having obtained this manuscript. Based on this, Bodhidharma was claimed to be the ancestor of Shaolin martial arts. This manuscript is full of errors, absurdities and fantastic claims; it cannot be taken as a legitimate source. (Lin Boyuan, Zhongguo wushu shi, Wuzhou chubanshe, p. 183)

While early legends associate Bodhidharma with Mt. Song, where the Shaolin temple is located, it is not until the 11th century that we see the appearance of a hagiographical record (in the “Jingde Record of the Transmission of the Lamp,” Jingde chuandeng lu) explicitly associating Bodhidharma with the Shaolin temple. No mention of Bodhidharma is found in any of the many stele inscriptions preserved at the Shaolin temple from the Tang dynasty.

Legend also associates Bodhidharma with the use of tea to maintain wakefulness in meditation (the origin of Chado), and favoured paradoxes, conundrums and provocation as a way to break intellectual rigidity (a method which led to the development of koan).

Nine years of gazing at a wall

Bodhidharma traveled to northern China, to the recently constructed Shaolin Monastery, where the monks refused him admission. Bodhidharma sat meditating facing a wall for the next 9 years, boring holes into it with his stare. Having earned the monks’ respect, Bodhidharma was finally permitted to enter the monastery. There, he found the monks so out of shape from lives spent hunched over scrolls that he introduced a regimen of exercises which later became the foundation of Shaolin kung fu, from which many schools of Chinese martial art claim descent.

Historically, it is unlikely that Bodhidharma invented kung fu. There are martial arts manuals that date back to at least the Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 220 CE), predating both Bodhidharma and the Shaolin Temple. The codification of the martial arts by monks most likely began with military personnel who retired to monasteries or sought sanctuary there. Within the refuge of the monastery, unlike on an unforgiving battlefield, such individuals could, confident in their safety, exchange expertise and perfect their techniques.

Bringing tea to China

Japanese legends credit Bodhidharma with bringing tea to China. Supposedly, he cut off his eyelids while meditating, to keep from falling asleep. Tea bushes sprung from the spot where his eyelids hit the ground. It is said that this is the reason for tea being so important for meditation and why it helps the meditator to not fall asleep. This legend is unlikely as tea use in China predates Chan Buddhism in China. According to Chinese mythology, in 2737 BC the Chinese Emperor, Shennong, scholar and herbalist, was sitting beneath a tree while his servant boiled drinking water. A leaf from the tree dropped into the water and Shennong decided to try the brew. The tree was a wild tea tree. There is an early mention of tea being prepared by servants in a Chinese text of 50 B.C. The first detailed description of tea-drinking is found in an ancient Chinese dictionary, noted by Kuo P’o in A.D. 350.