Finding Your Inner Master – Kigatsuku

By Shihan Henderson

For many students the practice of Kata, or forms, is very frustrating and elusive. Though they may practice and master the techniques and series of movements, deeper spiritual mastery is often out of reach. This may be due to a number of reasons. This paper is meant to identify some of those underlying reasons and to help avoid a crisis in training by bridging the gap of understanding for the martial arts student by comparing some of the similar aspects of both Kata training and traditional training of the Zen meditation student.

For many students the practice of Kata, or forms, is very frustrating and elusive. Though they may practice and master the techniques and series of movements, deeper spiritual mastery is often out of reach. This may be due to a number of reasons. This paper is meant to identify some of those underlying reasons and to help avoid a crisis in training by bridging the gap of understanding for the martial arts student by comparing some of the similar aspects of both Kata training and traditional training of the Zen meditation student.

Through the years, Kata has been held in the highest regard by many of the most influential Sensei and has been considered the main training form in many martial arts. Its influence on Budo is apparent as most Budo styles and schools incorporate Kata forms as a primary learning methodology. However, Kata often remains simply that – a method used to teach technique (waza), whereas it can and should be much more. That is, Kata should be the door that the student opens to lead himself onto a life long Zen journey.

When comparing the technical aspects of Kata against its spiritual aspects, it should be noted that technical mastery of the basic and advanced movements within the martial arts can be obtained within a relatively short period of time by any student of average capacity who shows a desire to learn and study. For arguments sake, and from personal experience in teaching, let us assume that this process takes somewhere from five to ten years of general martial arts training. Otherwise stated, the average Karatedo student will have mastered his physical technical training somewhere around the second to fourth dan (level) black belt. After this technical mastery has been achieved, new Kata forms will not provide the student with any further benefit unless he or she is willing to view them in a new light. That is, to see them as a spiritual exercise that can bring them closer to a fuller understanding of the nature of reality and their own true nature.

If the student is unwilling to do this, or not inclined to delve into the nature of this exercise, then more likely than not the student will become bored with the Kata practice and eventually will falter, and his overall Budo practice will thus suffer. This is true due to the fact that without a sense of the spiritual within Kata practice we are left simply with technique, waza. And waza is primarily concerned with efficacy in fighting. This in itself is fine and the student and teacher can spend many hours devoted to trying to derive the proper application (bunkai) of the Kata movements and what might be their fighting significance. Kata movements can often be viewed in several concurrent interpretations all of equal merit and the arguing and comparing of those interpretations can be very interesting and exhilarating. However, the analysis of the bunkai and its importance to the life of a fighter is short lived.

The physical nature of the body which lends itself to the sole study of Budo technique (Jutsu) or waza is limited. We all grow older and with time our own bodies age and become less strong. Even the greatest martial artist will one day grow old and become weaker and eventually die. So, needless to say, at some point the physical nature of Karate training can no longer remain the driving force of the martial arts study. For some this comes quickly and for others it happens much later in their martial arts career, but eventually it will come.

It is the opinion of the author that many advanced martial artists reach this point and enter into a type of crisis. Being in crisis and potentially not having a more advanced teacher to point the way to continued practice, these students and some teachers will often stop practicing all together. This is a great loss. They no longer derive any real benefits from practicing as they have mastered the physical techniques and the spiritual application remains outside their grasps. Being at this cross-road and not knowing which way to turn they become disillusioned with their training.

At this point, it is critical that the student realizes that a crisis is at hand. For many students this point in their career is not understood and they simply see themselves as having lost interest in their training. They take the attitude that it is time to move on to something new and/or they have matured beyond their martial arts. For some students they may pass through this point in their training without too much consternation and for others the metamorphosis seems almost impossible to complete and thus training stops.

As the title of this paper suggest, “Finding The Inner Master” refers to this process of dealing with this crisis point and moving beyond. The author believes that one successful teaching method to help students pass through this crisis point is to illuminate the similarities of other students who are following a Zen Path within non-martial arts schools. By doing this the underlying Zen practice of Budo and Kata, in particular, will become clearer.

The name Budo represents a “way”, that is the “do” portion of the word. If you are someone who practices budo (budoka) then you follow a spiritual path using Budo as your technique, the same way a Zen student uses the tools at his disposal within his own Zen school, ie: Zazen (meditation). Similarly, a Zen student may follow the tea ceremony or yet be a Zen gardener. Whatever the “do” may be the student needs to know and understand that the road he or she is traveling is a Zen Path.

Unfortunately, the first obstacle that many students face is that they simply practice “jutsu” and do not practice “Budo”. That is, they practice the application of the techniques and do not follow the spiritual path laid-out through Budo practice. As mentioned above, Budo without the “do” is simply a study of jutsu, that is: technique. And so they begin their practice learning various Kata and an assortment of techniques without the understanding that they are following a spiritual path. This is a critical road block and hurdle to deeper personal self knowledge and understanding.

In today’s world there may be ample reason for this. Firstly, it is much easier to sell a new student a package of martial arts lessons then initiate them on a life long Zen journey with Budo as their mantra. Moreover, many new students falsely believe that a fighting system that lacks a spiritual undercurrent is by definition more streamlined. For some, more streamlined translates into more effective. This interpretation is often taken as a selling point when compared to other traditional spiritually infused schools. Further, we see that as life becomes quicker and quicker paced and the day-to-day scheduling constraints are constantly increased, people look to streamline any of their tasks – their martial arts practice is no different. And who can blame them. We all feel the same pressures. Unfortunately, it is exactly the spiritual guidance from Zen study that they need in order to help them adjust and deal with these increased pressures of modern life. Zen training can help. Zen Kata can help and a Budo practice infused with Zen through the proper teaching and study of Kata is the perfect tool.

Another reason that many students opt for the streamlined approach to martial arts training is that they believe a traditional school will clash with their own religion. Some students almost automatically think that they should not try to practice Zen within their martial arts or Budo experience as they are practicing Christians, Jews, or Muslims and that Zen study will collide with their faith. This in itself is a very understandable concern. However, Zen is not a religion in the same sense as the aforementioned. Zen practice is not filled with any ideas, thoughts or philosophies. It simply tries to illuminate the underlying nature of reality through the practice of Zazen (sitting meditation), or in the case of a Budoka through Kata.

It may be confusing as to how spiritual mastery can be obtained from practicing the same Kata that enabled the student to gain technical mastery. At first glance it would seem that the purpose of Kata is to teach the technical material, which is true. However, Kata also has a higher goal and that goal is firmly based on spiritual development. Kata is important because like Zen it enables us to isolate and know our inner self, the same self that too often is absorbed in the machinations of the external world.

The technical study must come first and be mastered in order for the student to free his mind and intellect of the necessity to view and review each move within the Kata form. Technical mastery must firstly be achieved so that the mind is better able to clear itself in the same fashion that a Zen student clears his own mind during meditation (Zazen). The only difference is that the Kata meditation is dynamic (moving) while the Zen meditation, for the most part, is static (sitting). Most Budo students do not understand that Kata practice is moving Zen study. They have not made the connection or a teacher has not explained this fact to them. No one has opened this door for them so they simply see their Kata form as a series of geometric steps or like a dance chart.

Before comparing Zen studies with Kata training, it should be underscored that the word Kata refers to all things that are based on form. Thus, not just the technical material forms are Kata but everything that is performed within the setting of the practice hall (dojo) is Kata and should be executed with precision and awareness. Moreover, with experience everything in life becomes Kata and even the non-dojo, non-martial arts endeavors become Kata. Essentially, every moment of your life becomes Kata and a place for Zen. This is the evolution and goal of Zen Kata and is exactly the same for the non-martial arts Zen study. Far too often students see their martial arts training as being solely within the dojo. They do not understand that what they are learning is applicable to everything in their lives. However, as the student does mature you can often see this change take place within their understanding and attitude.

I have often joked with my own contemporary training partners that when I first started martial arts practice I would refer to my Karate life and to my other life. These two things were separate. With time and with much training these two distinctly separate activities merged and became one. My Karate life and my other life just became life. This is a very important point. In order to follow the Zen Path, no matter what way or “do” you chose, you must make this “leap of faith”. In your heart you must come to the realization that Karatedo, Aikido, Kendo, Judo, or Budo, is not simply something that you do but it is something that you are. Your spirit is alive with your “do”. You are it and it is you. This is the artist aspect of the term “Martial Artist” and it is essential if you are to walk the Zen Path using your particular martial art as your guide. Unfortunately, some students do not or are not willing to make this leap of faith. However, as in every spiritual endeavor a leap of faith is necessary in order to fully give yourself to your faith (art). Once you are able to do this many issues and road blocks will fall away.

For instance, many students complain about the number of repetitions that they must perform in order to master their Kata. Anyone who has made the requisite leap of faith and who sees their Kata form as their Zen koan (Zen riddle used to bring about awakening) would have no issues about performing it many times over. It is the same as a priest praying. The prayer is his own. It is him and he is it. And so he recites the prayer (or koan) over and over and over until it takes over his being, his essence. It stays with him all day and his mind reflects on its nature and beauty until at some time new underlying meaning and importance is found. In beginning our comparison to non-martial arts Zen training the student will be well served to keep this leap of faith in mind.

Let us now compare the similarities in training experience of the Zen and Budo student. When a Zen student arrives at his dojo his first duty is to remove his shoes and place them in parallel fashion with the toes facing outwards from the dojo hall. Afterwards, the student enters the room slowly and purposefully with the left foot forward. When leaving the dojo the student exits with the right foot first. Before taking his place the student raises his hands in a humble gesture of greeting. This gesture is known as gassho. Gassho is an expression of the student’s inner spirit, attitude and harmony. After gassho is completed the student finds his place by walking in a clockwise direction around the perimeter of the dojo.

Any student of martial arts will immediately see the parallel in the above Zen training entrance rituals to their own martial arts or Budo dojo. Shoes are taken off and hopefully placed in a neat and tidy fashion, entry salutations with bowing are made, the student finds his place on the floor in rank order with the least amount of distraction and the practice session gets underway. Beginner and intermediate students may not have realized that the above was a Kata form and most likely would perform the steps without giving much thought to what they were doing.

However, when your Budo or martial arts training takes on a higher purpose then each step becomes Kata. As a mental exercise, think about the difference between the entrance ritual of the average white belt student and a Shihan Master (above 6th Dan), the difference is obvious even to the uninitiated observer. For the Master, every move has a purpose. His entrance ritual prepares his mind for the Budo training in the same way as the entrance ritual prepares the Zen student and Zen Master for their own studies. Thus, as a beginner or intermediate Budo student you should pay particular attention to your entrance and exiting rituals as it is within these steps that your true training begins. This is mental training in preparation for physical training. It is your spirit awakening to the challenge of Budo training, don’t sleep walk through the steps – create awareness at every move.

Creating awareness at every move is also important because it can help to break the ordinariness of the day. During our work day we often go from one event to the next in a type of mindless haze like a robot completing tasks, often the same tasks we have done many times before. Creating a renewed sense of awareness in this environment is a good thing as it can bring us back into the true moment of our life. However, for the beginner and intermediate student it is of primary importance to be conscious of creating that awareness firstly within the dojo setting. Too many students arrive at the practice hall already flabbergasted by their day and move onto their martial arts training without thinking about what they are doing, or going to do. The student needs to mentally pause and take some time to center themselves. They need to calm their everyday spirit and prepare it for training. Without doing so the martial arts practice can take on a hurried pace and that would be detrimental to all students at large. The mind needs to quiet itself so that the student can focus his energies in one direction. For the Zen student that means focusing on their meditation, for the martial arts student that means focusing on their Kata.

One of the first and most important lessons a Zen student learns is silence. Though a martial art dojo differs from a Zendo in the ambient level of noise, martial arts students would be well served to limit the amount of noise that they produce when practicing. By noise it is meant the unnecessary noise that is just filler. Some noise is required since the exercises are dynamic and fatigue sets in and the body gasps for air, or there is a tradition of verbalizing the Kiai (spirit yell). However, the danger is that the martial arts dojo takes on the same characteristics of a gymnasium. Martial arts, though fun, should be taught and learnt in an atmosphere of sincerity and concentration. For most, excessive noise detracts from this. Each student should try not to let their attention stray to their neighbor and should remain focused on their lessons and Kata.

In the case of the Zen student, quiet is of the utmost necessity. It is the requisite atmosphere needed for the full concentration on their meditation as their breathing sinks them deeper and deeper. Moreover, and depending on the school, the Zen student may be actively meditating on a koan (Zen riddle) given to them by their Zen Master. Any unnecessary noise would only distract the student from their concentration and prevent them from developing awareness. Similarly, in the martial arts school too much noise can distract the students from concentrating on their lessons and developing both technically and spiritually. With constant distraction the student is unable to focus, without focus all is lost.

In the above we see the importance of breathing for the Zen student when he practices meditation. Focusing on the breath is an ancient tradition that some say goes back to the time of the Buddha. In order to quiet the mind and to create awareness the student follows his breathing counting the inhalations and following the exhalations. One method is to count these inhalations as odd numbers 1,3,5,7,9, and to count the exhalations as positive numbers 2,4,6,8,10. This practice creates a rhythm and is something that even the beginner student can practice. All extraneous concerns are released and the student merely focuses on his breath. This is also very important for the martial arts student. Within Kata practice the proper inhalation and exhalation will determine the cadence of the Kata. The cadence of the Kata is its rhythm. With the proper rhythm the Kata will come alive and develop into sections that as groups of techniques will represent series of combinations that may be used in self-defense (goshin-jutsu). However, in a similar fashion to the Zen student, the proper breathing within the rhythm of the Kata will also enable the student to become more centered. Increased centeredness will increase awareness that will follow into a more profound understanding of the practitioner’s place within the Kata and thus within the larger environment as a whole. Breathing is the essential element to your Zen training. It is the comfortable shoes you wear as you walk the Zen Path. All students need to understand the importance of breathing and how it affects the physical and meta-physical aspects of their training.

In many martial arts schools the day’s practice is opened and closed with a short meditation, (Mokuso). Many students do not understand the purpose behind this meditation period and it is often the first thing to be discarded in commercially oriented schools. Students need to be instructed as to the Zen nature of this meditation and they should be instructed as to the proper way to breath and sit during this meditation period. Opening and closing meditation completes the wheel of training for the day and links the concepts of the three minds (Mittsu no kokoro): Zenshin (preparatory mind), Tsushin (concentrating mind) and, Zanshin (remaining mind). That is, the opening meditation is the Zenshin phase of training. The student prepares himself for the day’s or evening’s training. He reflects on what he needs to practice and focus upon, what he needs to fix or improve, he gets his mind and spirit ready for training. Tsushin represents the actual physical training. The mind is focused on the exercises of the day. Distractions are kept to a minimum and the student is fully immersed in his training. Closing meditation is the Zanshin phase of training where the student reflects on his performance for the day. He considers what lessons or techniques were difficult and which went well. He makes mental notes on what he must improve during the next practice session. It is very important that students understand Mittsu no kokoro if they are to create awareness in their Budo and Zen training. Without this understanding and practice students will run the risk of sleep walking through each practice session repeating old mistakes and missing their personal gains.

In the above we see that both the Zen student and the martial arts student must be preoccupied with posture in order to meditate correctly. Out of all technical aspects posture is of paramount importance. For the Zen student holding proper posture in Zazen for hours at a time can be daunting and if the posture is incorrect then the meditation will be flawed. The Kata of the martial arts student is a summation of many postures that need to be executed correctly so that mastery of the entire Kata can be obtained. Thus, we see that a quest for enlightenment for both the Zen student and the martial arts student starts with a preoccupation on posture and breathing.

The next point that directly affects the environment of the dojo is that of questioning. Though some questioning is appropriate far too often students ask too many questions. This may be so for many reasons: the student may wish to impress the teacher, the student may be generally curious or confused, or the student may be nervous and talking calms them down. Whatever the case may be, too much questioning from the student is detrimental to the learning path. Both Zen mediation practice and Kata practice are experiential pursuits. That is, you have to do them, not talk about them. You may be able to talk and read about them, but you must experience them to be able to understand them on a basic intrinsic level. Through constant practice, not questioning does the student grow. So the student needs to quiet themselves and get busy meditating. In fact, in many Zen schools, the student is allotted only a few minutes each session with the teacher, (Dokusan). And this time is used by the teacher to ascertain the progress of the student. Students are encouraged to keep their questioning to a minimum. Martial arts students should keep in mind that excessive questioning can actually hinder their progress as they are placing verbal roadblocks in their way and it distracts their mind from discovering the true nature of the Kata.

The other important similarity of Zen practice and Kata practice is that contrary to popular belief both are group activities. That is, within the confines of the dojo the student practices along side other students and in this fashion is bonded and inter-linked into the greater whole. Further, even when practicing outside the dojo the student remains linked metaphysically to the other students. As Zen Master Dogen has stated, “When someone practices Zazen, even if only for 20 minutes, it is as if the whole world were practicing Zazen.” This statement though centered on the power of Zazen also reminds the student of the palpable nature of meditation. Kata being dynamic meditation shares this fact. So when you practice Kata the link that you have with your fellow students is re-energized and the natural system that connects each student to the whole benefits.

The next practical and important similarity between Kata practice and Zen practice is that the student must have a purpose. This may sound self-evident however many students are lost on this point. That is, the Zen student may think at first that he or she should be thinking about something or nothing (Mu). Often, the student is not sure what to think. As well, martial arts students often do not have a clear purpose and come to their studies not knowing what they wish to achieve. For the Zen student a focus such as studying a koan, or focusing on breathing, or sitting in awareness can be the purpose. For the martial arts student the purpose may be a focus on breathing or a fuller awareness of the geometry or cadence of the Kata or a greater examination of the intricacies of the movements (techniques). In both cases, the student’s teacher should also be aware of what the student’s purpose is. There should be communication between the student and teacher so that feedback can be given to the student in order to assist them in their growth.

So far we have identified what are really lower-level similarities that lay the foundation for a greater comparison of higher level similarities between the two practices. When the basics of etiquette, posture, breathing and reflection are mastered and the koan and kata are practiced several hundreds if not thousands of times then the student may begin to transform. This transformation may be subtle or it may come as a surprise quickly. However, it is only with experience and dedication that it ever comes. When a martial arts student studies a particular Kata over and over and over it is no different than a Zen student studying the same koan over and over in his mind reflecting on it a thousand different ways. Zen koans are riddles and as such they force the student to go beyond logic. The confusing nature of the koans causes the student to become both physically and mentally exhausted as he wrestles with apparent contradictions in his mind. A favorite koan of the author is to ponder on the question: “Before your mother and father were born, what was your nature?” Only once the student has exhausted his logical mind can he or will he be able to reach a point where the intuitive nature of the koan comes through. This occurs only after an exhaustive examination of the koan takes place. The Zen student becomes the koan and the koan becomes him. He lives with the koan day and night trying to grasp its understanding.

To the surprise of many martial arts students the same is true for Kata practice. The martial arts student must perform his exercises or Kata until he has exhausted his physical energy. Many martial art masters state that true learning only begins at this point of exhaustion. For the Kata practitioner several things happen. With exhaustion many issues fall to the wayside. Unnecessary steps and movements are economized. The performance becomes reduced to only the necessary steps required to accomplish the goal. Economy in motion becomes the overarching rule of Kata. With economy in motion comes economy in thought. With the proper practice the student thinks and reflects on only the most essential elements of the Kata. The mind becomes a truer reflection of the perfect Kata until a point where physical and mental exhaustion brings forth a new understanding of the character of the Kata that might not have previously been known or seen. As each koan teaches a new lesson so does each new Kata. And once that lesson has been discovered the student can try to peel back the onion skin of the other Kata and see how each fits into the greater whole.

But beyond this point the martial arts student begins to reflect on the Kata even when not physically performing Kata. That is, the Kata has become such a part of his being, or he has become such a part of the Kata, that it lives with him at every step. When the student has reached this stage in his growth he is able to view himself performing his Kata outside of his own body. He can project his Kata anywhere and at anytime without physical movement. As in Zazen meditation (Mokuso) his Kata is now his koan and he is able to play back the Kata in his mind’s eye both as the player and as the observer. This is a full dimensional view of Kata. There no longer is a distinction between the Kata and I, subject and object have been merged as one. This state of deep collectedness and absorption both inside and outside is called Zanmai and in Zen circles is a sign of approaching enlightenment. At this point the practitioner/student can experience a deep and complete relaxation which also can transform the experience of pain. Previously felt pain from training may begin to slip from consciousness. The author has experienced this during the completion of The Camino de Santiago in Spain, the ancient Christian pilgrimage of 1,100 kilometers. Excessive daily walking brought on extreme fatigue which produced great muscular pain until at one point that pain was breached and the walking just happened.

The same is true of the Zen student and he will begin to reflect on his koan even when not in active meditation. The student is truly becoming the koan and working with it day and night. This is the foundation for further spiritual growth. At this point the student must continue to practice, he must continue to push himself further along the path of awakening by continuing his kata or koan study. At some point the consciousness will be filled with the kata or koan and then it will overflow and be emptied. This process was identified by O-Sensei Ueshiba of Aikido in his early days when he stated that at one point he had forgotten all his martial arts training.

For both the Zen student and the martial arts student the benefit of Zen training comes from turning within and sensing your own true nature. When followed with dedication and sincerity the student will become a master and particular benefits will develop. Through a dedicated Zen practice either through Kata or Zazen the student will develop meditational powers and insight, known as Joriki and Chi-e. Joriki is known as the ability to quiet the normally distracted mind and establish a type of spiritual balance. Chi-e is insight and is the intuitive side of realization. As the student’s meditation continues to deepen their spiritual balance and intuitive insight will increase. This is the practical benefit of both Zen and Kata practice. Satori, or awakening, is the state where intuition supersedes intellect and has often been described by Zen Masters as indescribable. A sudden flash of light or a deep sense of understanding that quite literally rocks the student’s world. In fact, many representations of the Buddha in sculpture show him touching the ground while meditating. This represents the fact that The Buddha’s meditation was so profound that he needed to touch the ground in order to reference himself.

The above state of satori or awakening is something that all beings are suppose to be able to achieve. The Buddha himself said that all beings have inherent Buddha nature and can achieve enlightenment. However, from a martial arts and Zen standpoint there is also another state that is of great value and perhaps more relevant in the near term than Satori.

As the title of the paper suggest Zen meditation whether active (Kata) or passive (Zazen) helps the practitioner to find the Inner Master. The road to finding the Inner Master produces specific benefits to the practitioner such as: moral transformation, meditational strength (Joriki) and intuitive insight (Chi-e). When these have occurred and when the student is sincere in his devotion to study and continues to practice he will eventually come to a place where he will see the true nature of his being. The term in Japanese is called kigatsuku – “that is how I am!” Kigatsuku is not the powerful energy releasing experience of Satori but a gradual ever increasing understanding of one’s true nature. It is a deeply moving experience and can be life altering. Kigatsuku is your Inner Master and this is achievable to all martial artists who are willing to devote themselves to a dedicated, sincere and life long application of their art.

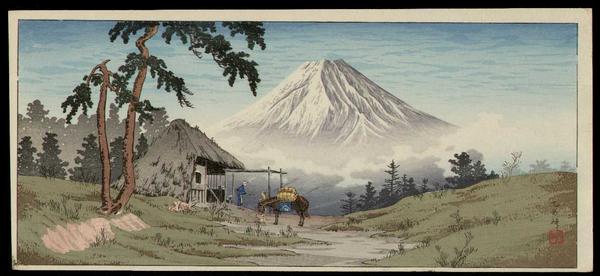

For many martial artists their journey along the Zen Path is cut short. Even for some advanced students and teachers their Zen journey comes to an end prematurely as they have not had the benefit of a teacher who can point them in the direction of the true Zen Path and illuminate for them the specific benefits that can accrue through full dedication and by taking the leap of faith required after technical mastery has been achieved. For all martial artists the quest to find their Inner Master is a real quest, not an esoteric search for enlightenment. With an understanding of the concrete benefits that can be obtained and following a well laid-out path using dynamic Zen meditational Kata training every martial art student can find their Inner Master. This is the real goal of the martial arts. The road is not an easy one to follow. It contains trials and tribulations and a myriad of challenges. However, with dedication and sincerity and a leap of faith you can find your true nature and that Inner Master (kigatsuku) and along the way you might just find enlightenment as well ! Take one step at a time and soon you will be standing at the top of the mountain.