As Budo teachers we often reflect on why individuals are attracted to the martial arts. We often believe that they are attracted because they are looking for direction in life. That is, they are typically looking for something to which they may apply their talents in a way that is typically not found in the mundane routine of daily life. What they tend to seek is a challenge where they may grow physically, intellectually and spiritually.

When a new student enters the dojo and begins his or her martial arts journey one of the first things that they encounter within their new system is the Dojo Kun: the main set of guiding principles. Typically, each system or “ryu” has a set of Dojo Kun and often individual schools within a system will also have their own set of Dojo Kun that are particular to the inclination of the head Sensei of that school. Within the Shorinjiryu Kenkokan lineage we have been provided a set of Dojo Kun from the founder, Kaiso Dr. Kori Hisataka for the direction of all Shorinjiryu students, they are:

- Maintain propriety, etiquette, dignity and grace

- Gain self-understanding by tasting the true meaning of combat

- Search for pure principle of being: truth, justice, beauty

- Exercise a positive personality, that is to say: confidence, courage and determination

- Always seek to develop the character further, aiming towards perfection and complete harmony with creation.

We can say that Kaiso Hisataka considered these principles to be of paramount importance and is why they have been codified as such. Otherwise said, these principles do not only signify what Kaiso Hisataka believed to be important for daily direction of the self but in creating them Kaiso Hisataka provided each and every Karateka or Budoka a glimpse into the principal elements of his own character and make-up. In short, the Kenkokan Dojo Kun represent Kaiso Hisataka’s world-view and by considering them we also acknowledge his inner character and through that acknowledgement we internalize his deepest held beliefs and moral teachings. Kaiso Hisataka did not simply give us a set of principles to follow he gave us part of himself to emulate.

Further elaborating on the Dojo Kun we must keep in mind two critical characteristics that are paramount to an understanding of their underlying nature: time and timelessness. The Dojo Kun were created by Kaiso Hisataka after the great destruction of World War II when he felt that Japan had lost its way and that the people of the nation had become demoralized. This coincides with the creation of the system of Shorinjiryu Kenkokan and the location of the first Hombu dojo. Kaiso Hisataka essentially created the Dojo Kun to help reinvigorate the character of both individuals and the nation. In this respect the Dojo Kun are very much tied to the post-war rebuilding era of Japan. This represents the first characteristic that is static by nature being wholly related to the cultural imperatives of that particular moment in history.

The second critical characteristic of note is the fact that Kaiso Hisataka was providing a set of guidelines to fight against demoralization and as such he was looking for a set of immutable and timeless principles. That is, he was searching for principles that would live and stand the test of time and that were to a certain extent self-evident, at least to the practiced Budoka. Interestingly, in order to ward-off the demoralization of society that he had observed he created a set of universal morals, albeit at first glance seemingly universal for and oriented toward the Budoka. This is the second characteristic that is predominantly fluid by nature in so far as the Dojo Kun are meant to be handed down generation after generation to provide on-going timeless guidance. Thus, the Dojo Kun created by Kaiso Hisataka can be characterized as being born of a specific time and place and yet applicable to all persons no matter the era. They contain the essential characteristic of any true set of morals, that is, they can be considered universal.

Similarly, throughout history societies and the important players within them have essentially tried to do the same thing. From the all important commandments of the principal religions to the recited guidelines of the many lay and secular organizations around the world, principles have been provided that seek to remind us of our better or higher nature so that in times of peril and stress we will act and react appropriately. Within the western cultures these have predominately been of the Abrahamic variety handed down by the three great and inter-related religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Though in recent years many in the West have also been influenced by the fundamental virtues of the Eastern mysticisms, being: Hinduism, Buddhism and Shintoism.

Again, what these religions or mysticism have in common is that they all focus on the immutable and the self-evident, but not necessarily the obvious. They bring to the fore a set of reasoned principles that identify the essence of what it means to be and to act human that once understood becomes an essential part of the participant. The participant is forever changed by the very act of conscious adoption of the principles. That is, one can venture to say that once accepted and internalized by the participant a type of spiritual transformation takes place.

Now, you might ask yourself how the principles of the Dojo Kun listed earlier may be considered spiritual in nature when on the surface they appear to be secular in character. The answer to this important question is that the spirituality is inherent or manifest itself in the fact that the principles connect the inner reflection of the self (the subject, ourselves) to the understanding of the other (the object, the other person). The principles connect the one with the many and create a sense of shared humanity and shared community and through this we are fundamentally changed. The other is no longer just out there as an isolated thing or object to be used by us, it has become humanized by being connected to our own psyche, both sympathy and more importantly empathy is created for the other and this is nothing short of the mystical. As some would say God lives within the inter-relationships we keep with others. This sentiment is manifest in the examples of such persons as Mother Teresa and Mahatma Gandhi who both emphasized the connectedness between individuals as being the essential element of humanity. In this sense, the focus of all moral guidelines is on the interconnectedness that we share with the others around us. Reflecting back on the Dojo Kun we see that this is true in so far as it admonishes us to maintain grace and seek harmony with creation, creation being a synonym for the others around us.

Turning back to the main title of this article, “The Universality of the Dojo Kun”, we can further compare the Dojo Kun of Kaiso Hisataka to some well-known and well considered principles. Again, for the purposes of discussion our historical reference points are the Abrahamic and Greek traditions for which most readers are familiar. Within these traditions a set of seven heavenly virtues were developed. Perhaps as a commentary on our own culture each of these virtues has an identified vice that seems to be more well known. The virtues and vices are listed below in table form with their Latin and Greek historical translations.

As mentioned, the seven deadly sins or Cardinal sins are typically better known and are in fact older first appearing in the Book of Proverbs (Mishlai) as stated by King Solomon when reciting the seven things that the Lord hateth the most. These were further refined by the 4th century monk Evagrius Ponticus who became an Ascetic monk in the lineage of the Dessert Fathers under Rufinus in Nitria, Egypt as depicted in the Philokalia, the important ancient account that is a fundamental text of Orthodox Christianity.

The seven heavenly virtues were a somewhat recent addition introduced around AD 348 by Aurelius Prudentius Clemens a Roman Christian poet who lived in northern Spain. His work became very well known in the Middle Ages and the seven heavenly virtues were considered the basis of the code of honor (chivalric virtues) of the various sects of knights as described by the Duke of Burgandy in the 14th century, which are: Faith, Charity, Justice, Sagacity, Prudence, Temperance, Resolution, Truth, Liberality, Diligence, Hope and Valour. In fact, the symbol of the Order of St. John, an eight pointed cross, symbolizes this clearly as the four main arms represent the cardinal virtues of: Prudence, Temperance, Justice and Fortitude while the eight points represent the beatitudes, being: Humility, Compassion, Courtesy, Devotion, Mercy, Purity, Peace and Endurance. It is believed that these chivalric virtues were critical in the influences of later Victorian era perceptions with regards to the proper etiquette of Gentlemen.

Theologically speaking, we can break-down the virtues as natural and supernatural. The three “supernatural” virtues are: Faith, Hope and Charity, as in: Faith in God, Hope of Receiving and Charity or Lovingkindness towards one’s neighbors. Faith in God reflects the thought that a lack of faith may give rise to incredulity. Hope of receiving reflects the thought that a lack of hope will give way to despair or cynicism, while a lack of Charity or Love may give way to hatred or wrath. Lovingkindness also relates directly to the Eastern mysticisms as it takes a primary place in the construct of Buddhism particularly as practiced by the Dalai Lama. St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) who is considered the foremost theologian of the Christian church and one of the 33 Angelic Doctors identifies the four main “natural” virtues that are binding on all persons as: Prudence, Justice, Temperance (restraint) and Courage.

St. Thomas Aquinas is a noted Aristotelean and Scholastic and took his cue from the writings of Plato in “The Republic” who identified these virtues with the varying classes of society. In the Phaedo or “Death of Socrates” by Plato we learn that Socrates held certain virtues as the most dear and those were generally considered to revolve around the thought of self-development over material wealth and a sense of community or connection with others. Socrates believed that people possessed certain virtues and these were representative of the most important qualities a person could have and that the ideal life was spent in search of the “Good”. This last point of Socrates is clearly represented in the Motto of Shorinjiryu Kenkokan also developed by Kaiso Hisataka that reads: “Spiritual Development of Individuality in Mind and Body” as well as directly represented by Dojo Kun #5, i.e.: development of the character.

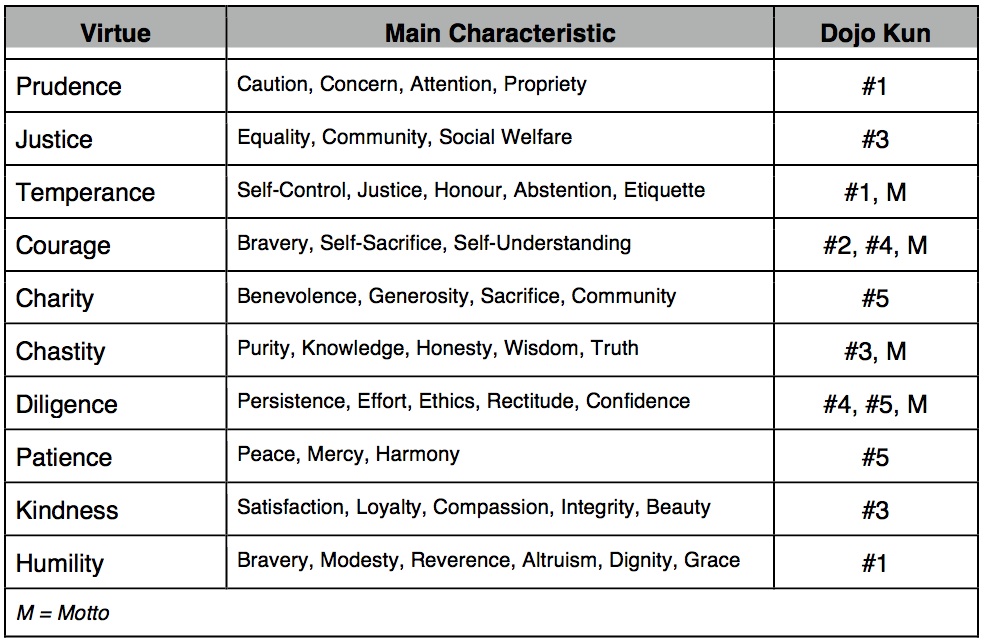

By now the reader should see a trend in the narrative that points to a set of generally understood cardinal or principal virtues that are typically considered binding on all persons as revealed by sages from various cultures across the eras. These start with the ancient Greek and Hebrew writings that inspire Christian theologians later being adopted by the Chevaliers of the middle ages and refined by the Gentlemen of the Victorian age to arrive in modern vernacular as generally useful to the present day citizen. They are also mirrored in the underlying constructs of the Eastern mysticisms. Mapping these virtues on to the Dojo Kun as given by Kaiso Hisataka again reiterates and elucidates the universality of the underlying lessons that he wished to teach and we see that all the main virtues as earlier discussed are covered by his teachings.

In closing, one can say that it does not come as a surprise that a teacher as important as Kaiso Dr. Kori Hisataka, who gave so much to so many Budoka, reflects in his teaching the ever present and important lessons shared by the many notable historical figures discussed. In this he is in the presence of the learned and scholarly through the ages and shares their main characteristics. He like the others, have provided us with timeless direction for cultivating our better natures to ultimately live more harmoniously with one another while striving for development of the self. For this we need to be grateful and appreciative. All Budoka through the teachings of the Dojo Kun should reflect on both the importance of the lessons and on the generosity of the man as examples worthy to follow.